- Three officials from the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps have been put on a US sanctions list for links to alleged human rights abuses

- XPCC has stakes in more than 800,000 companies and groups in 140 countries

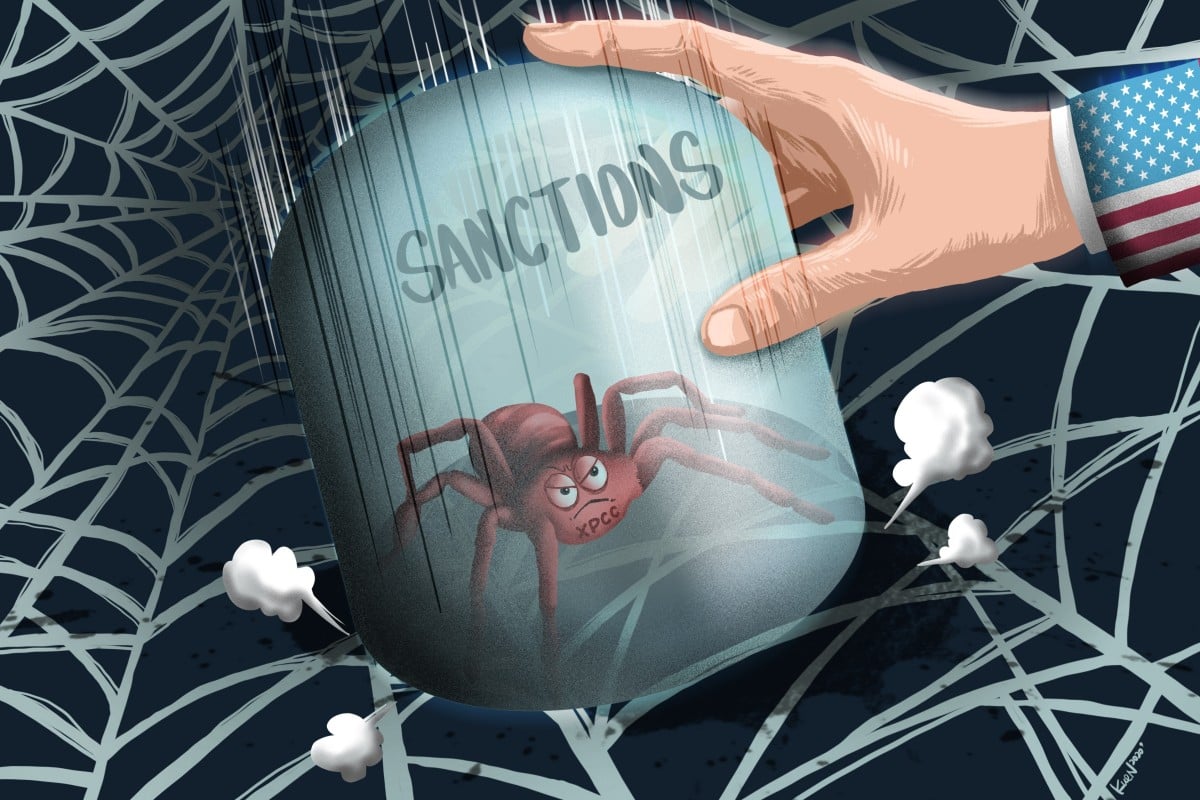

Illustration: Lau Ka-kuenOne of China’s most secretive and expansive organisations, the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps, has moved into an international spotlight it would probably rather avoid after the entity and three of its officials were put on a United States sanctions list for links to alleged human rights abuses.Known as XPCC, the organisation operates in the area of China that shares its name, Xinjiang, an autonomous region three times larger than France in China’s far west that borders Afghanistan, Pakistan and India.

The US move against XPCC and its majority owned subsidiaries could be the biggest case in the history of the Office of Foreign Assets Control, the agency under the US treasury department that enforces financial sanctions, for the potential number of holdings affected. The sanctions have multiple implications for XPCC, from choking off bank loans to curbing its farm exports, such as cotton and tomatoes. They could also threaten its investments.

XPCC, which is involved in a myriad of industries, from construction and infrastructure to property and farming, has stakes in more than 800,000 companies and groups in 147 countries, according to US consultancy and commercial intelligence firm Sayari, which prepared a report on the conglomerate’s structure.

The sanctions are linked to what China’s authorities call re-education camps for local Uygurs and other ethnic minority groups in Xinjiang, but what the US and United Nations have said are forced labour internment camps holding as many as 1 million people. Legal experts said enforcement of the sanctions would face challenges due to the sheer size of XPCC, dubbed a “state within a state” by China scholar Thomas Cliff at Australian National University.

That description seems to fit with how XPCC sees itself. According to a 2018 report by the privately held organisation, it reports its revenue as GDP, listing US$5.88 billion in net exports as part of its total GDP of 251.5 billion yuan (US$36.4 billion). It functions like a government in running schools, policing and health care facilities across a number of cities in Xinjiang for its employees and their families.

Fred Rocafort, a former US diplomat to China who now works for international law firm Harris Bricken, said the sanctions were a positive development in the US tackling what is happening to Uygurs in Xinjiang, but taking on the XPCC was still a surprise.

“It’s a big deal. I was slightly surprised in terms of the magnitude of this action,” he said. “It’s comparable to sanctioning a Chinese province or a very large Chinese city … There are probably not many entities in China, whether they are political or business, which has that size. [XPCC] is a weird beast.”

XPCC did not respond to four email requests for comment on the sanctions.

A 2018 report by Uygur Human Rights Project said XPCC had effectively colonised Xinjiang. Photo: Reuters

Most of XPCC’s investments are managed by XPCC State-owned Asset Management Co, itself a wholly owned subsidiary of the parent company, according to Sayari. The investments include 13 publicly traded companies in China, such as Xinjiang Chalkis Tomato Products and Xinjiang Yilite, a liquor company.

The sanctions by the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) cover the organisation and its current and former officials Chen Quanguo, Peng Jiarui and Sun Jinlong. This puts them on the Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons list, which bans US persons or entities from receiving or providing services and property of XPCC and its majority-owned subsidiaries.

Founded in 1954 by Communist Party general Wang Zhen under orders from Mao Zedong, XPCC started as a paramilitary organisation at a time when the Turkic-speaking Muslim minority Uygur people made up three-quarters of Xinjiang’s population, according to the 1953 national census. Initially, XPCC mostly employed decommissioned soldiers and was tasked with defending China’s northwestern borders and developing the frontier by reclaiming farmland and building infrastructure, like roads and bridges.

It now has 14 divisions and over 170 regiments and employs or supports 3.1 million people, mostly Han Chinese, according to government statistics. Han Chinese make up close to 40 per cent of Xinjiang’s population of about 22 million, according to the statistics.

XPCC is a secretive organisation and gaining access to its operations is difficult even for those within China, according to scholar Bao Yajun who wrote a paper on XPCC in 2018. The organisation has a military structure and reports to both the Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region’s government and the central authority in Beijing.

The XPCC faced challenges such as a slowdown in population growth and unprofitable businesses, but Beijing continued to fund the organisation, covering over 90 per cent of XPCC’s budget in recent years, Bao wrote. This was because of its importance to Xinjiang’s governance and its role in the Belt and Road Initiative to expand trade and infrastructure from the area into Central Asia, he said.

XPCC has faced accusations of human rights violations from other groups.

A 2018 report by Uygur Human Rights Project said XPCC effectively colonised the region through large-scale Han migration, demolition of Uygur homes and suppression of religious minorities by closing mosques and religious schools.

Amid worsening tensions between China and the United States, Washington has increasingly taken action against Chinese organisations and individuals for human rights abuses. Since October 2019, XPCC has been banned from receiving US technology or goods.

After the Uygur Human Rights Policy Act 2020 was passed by Congress in May, several Chinese officials and the Xinjiang public security bureau were also sanctioned for their role in the alleged human rights abuses. They included Chen Quanguo, the top Communist Party chief of the Xinjiang government who oversees XPCC, and officials with from the region’s public security bureau. Chen has been called the architect of the crackdown on ethnic minorities in Xinjiang.

China’s foreign ministry spokesman Wang Wenbin condemned the US sanctions, saying on August 3 that XPCC had made significant contributions to ethnic unity and security.

Xinjiang dominates China’s cotton production and XPCC produced about 2 million tonnes of it in 2018. Photo: Xinhua

In contrast, Nury Turkel, a lawyer and Uygur rights advocate who sits on the US Commission on International Religious Freedom, said the sanctions on XPCC put US companies on notice about the ethical and legal risks of doing business in Xinjiang.

A 2020 report by the US Congressional-Executive Commission on China said companies such as Adidas, Calvin Klein and Campbell Soup were suspected of receiving goods from suppliers in China accused of using forced labour.

“Now, no business can claim ignorance of China’s oppression of the Uygur people,” Turkel said. “We hope the sanctions signal to other Chinese officials that there are costs associated with taking part in the Communist Party’s repression of religion. The world is watching and we know which officials and entities are responsible for the abuses against the Uygur people.”

International banks may also restrict dealings with XPCC now that it is a sanctioned entity, according to trade lawyers.

The US treasury department is likely to focus on those providing material support to XPCC’s rights abuses in Xinjiang, according to Sarah Wronsky, an international trade lawyer with US-based law firm Reed Smith, who highlighted the risks to banks and the questions they might be asked.

“What are the banks doing that could be construed as ongoing abuses? Is the bank providing a loan, that is going to finance XPCC’s construction of an internment facility or is the bank financing XPCC’s purchase of surveillance equipment? That’s going to be heavily scrutinised by the Office of Foreign Assets Control [OFAC].”

The penalty for violations could see banks becoming specially designated nationals by the OFAC themselves, which would effectively shut them out of the US financial system, Wronsky said. She said her firm was seeing more activity than usual as banking clients sought guidance on the implications of US sanctions.

Trade in agricultural products could also be hit. Xinjiang dominates China’s cotton production and XPCC produced about 2 million tonnes of it in 2018 or about a third of the country’s total, according to company figures. China is also the world’s largest tomato exporter and XPCC companies lead tomato farming in the country.

US and Chinese customs data show that after the Uygur Human Rights Policy Act was passed there was a rush of John Deere cotton-picking machinery being exported to China before the sanctions took effect, most of which would wind up in Xinjiang, the South China Morning Post reported earlier.

“As an ethical matter, if you’re dealing with the XPCC, if you’re in Xinjiang in any form, you are way too close to the human rights issue,” former US diplomat Rocafort said.

US sanctions could also affect XPCC’s joint ventures in places such as Africa and Ukraine.

“When you take into account that from a secondary sanctions perspective, another foreign person can also be designated just by providing material financial support or technology to XPCC or its subsidiaries, it really opens up a broad range of potential risks both for US businesses and foreign businesses,” Wronsky said.

Shih Chienyu, a lecturer on Central Asia relations at Taiwan’s Tsing Hua University, said the sanctions could cut off international trade for XPCC, essentially reducing it to “back to its basics”, in other words, mainly operating within China.

But he said he did not think the sanctions would have an immediate impact on XPCC or Xinjiang.

“I think Beijing may still be considering the sanctions and other hawkish gestures as a political move [by the US] and not an economic one. It is not about turning off the tap to make you die of thirst yet. That’s the US attitude towards Iran but I don’t think this is America’s goal for China.”

Rocafort agreed, saying the US was limited in what it could do to have an impact on what happens in Xinjiang or in China generally over human rights.

Rocafort and Turkel both said a boycott of the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics would be a more concrete gesture.

“We urge President Trump to publicly express concern about the ongoing crackdown against Uygur Muslims and other religious communities and to make clear that US officials will not attend the games if religious freedom violations continue,” Turkel said.

source– south china mornig post

Comment