It was one of the heaviest bombardments in history. A shock-and-awe campaign of overwhelming air power aimed at bombing into submission a determined opponent that, despite being vastly outgunned, had withstood everything the world’s most formidable war machine could throw at it.

Operation Linebacker II saw more than 200 American B-52 bombers fly 730 sorties and drop over 20,000 tons of bombs on North Vietnam over a period of 12 days in December 1972, in a brutal assault aimed at shaking the Vietnamese “to their core,” in the words of then US national security adviser Henry Kissinger.

“They’re going to be so god damned surprised,” US President Richard Nixon replied to Kissinger on December 17, the eve of the mission.

In what would become known as “the Christmas bombings” in America and “the 11 days and nights” in Vietnam (no bombing took place on Christmas day), swathes of Hanoi were obliterated.

An estimated 1,600 Vietnamese were killed amid some of the most harrowing scenes of the conflict, in an operation likened by some to the Hamburg raids of World War II for the sheer scale of the destruction and civilian death toll.

The devastating losses were not all one way. At the same time, the United States Air Force sustained losses that today would seem unfathomable. Fifteen B-52s – the pride of America’s fleet – were shot down, six in one day alone, and 33 airmen lost.

Tragically, some believe all these deaths were largely in vain, with historians to this day debating the extent of the operation’s influence on the wider conflict.

In the aftermath of the operation, both sides claimed to have come out on top – Washington claiming it brought the Vietnamese back to the table for peace talks and Hanoi painting it as a heroic act of resistance in which it took everything its foe had and still remained standing.

But if the fog of war made it hard to judge those claims, half a century on it has done little to dim the memories of the the US airmen who can still recall flying through the North Vietnamese air defenses.

“It almost felt like you could walk across the tips of those missiles in the sky there were so many fired at you,” recalled one retired US airman.

The flak was so bright, he said, you could “read a newspaper in the cockpit.”

Death at Christmas

The airman, interviewed by CNN to mark the 50th anniversary of the “Christmas bombings,” recalled a mood at his base that was anything but festive.

To give the the best cover possible, the bombing missions were conducted at night, with the B-52s flying out of U Tapao, Thailand, and Andersen Air Force Base, Guam. Because those that made it back to base would land in darkness, the crews would not realize until breakfast the next day who among their colleagues had failed to return.

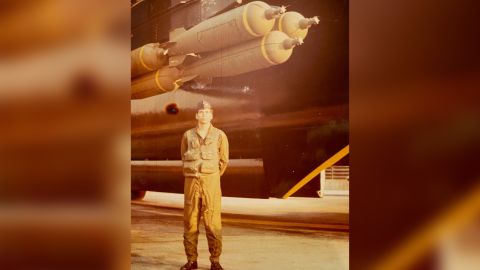

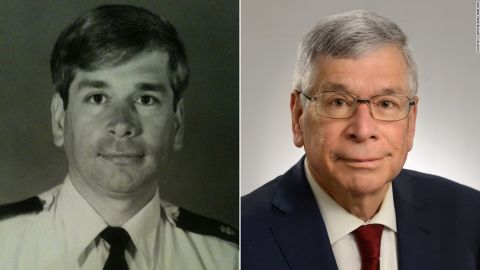

“You’d see the trailer next to yours with doors open on both ends and airmen loading (the occupant’s) personal belongings into a trunk to be shipped back to their families, so you knew that crew didn’t make it,” said Wayne Wallingford, an electronic warfare officer based in U Tapao who flew on seven of the 11 raids B-52s undertook over Hanoi.

“It was pretty sobering to see that.”

Over the 12-day period that grim ritual was performed 33 times.

But while the US Air Force’s losses were unprecedented, so too was the carnage caused by the B-52s.

“The resulting physical destruction was staggering: 1,600 military installations, miles of railway lines, hundreds of trucks and railway cars, eighty percent of electrical power plants, and countless factories and other structures were taken out of commission,” wrote Vietnam War historian Pierre Asselin in his 2018 book, “Vietnam’s American War: A History.”

“The Linebacker bombings crippled the North’s vital organs, obliterating the results of its communist transformation, and its ability to sustain the war in the South by extension,” Asselin wrote.

Such was the devastation that one Soviet diplomat warned that North Vietnam faced becoming “a wasteland.”

‘To this day, they smell the bodies’

The human cost on the ground was almost indescribable.

Duong Van Mai Elliott, a Pulitzer Prize finalist for her novel recounting her family’s experience, “Sacred Willow: Four Generations in the Life of a Vietnamese Family,” said the Christmas bombings were her relatives’ most frightening experience of the whole war.

“The buildings shook,” Elliott said. “They thought they were going to die.”

“Those who survived told me when they went out to look, they found dead bodies lying around,” she said. “To this day, they can still smell the rotting bodies.”

In one area of Hanoi, Kham Thien, 287 people were killed in one night alone – mostly women, children and elderly – and 2,000 buildings destroyed by US bombs, according to the Vietnamese newspaper, VN Express International.

An Agence France Presse journalist, who visited Kham Thien shortly after the US bombing, described a scene of “mass ruins … desolation and mourning.”

“On Kham Thien some houses still stand, but many of these are without roofs or windows. Dozens of craters, some 12 yards in diameter and three yards deep, pockmark the area,” Jean Leclerc du Sablon wrote in a dispatch that appeared in The New York Times on December 29, 1972.

One survivor in particular caught his eye.

“On a pile of ruins, an old woman held her hands to her face and chanted hauntingly, in near religious tone: ‘Oh, my son, where are you now? May I find you to bury you. Americans, how savage you are.’”

Nixon’s bid for ‘peace with honor’

The driving force behind the Christmas bombings was a recently reelected President Richard Nixon, who was keen to wrap up America’s involvement in an unpopular war before the beginning of his second term in January.

Nixon had been reelected just over a month earlier on a promise to attain “peace with honor” in Vietnam – where the US had been fighting since 1965 – and was stung when talks with North Vietnam suddenly fell through.

He warned Hanoi it would face consequences if it did not return to the negotiating table in good faith and ordered Linebacker II even as a new set of demands were being sent to the North Vietnamese.

The Air Force’s reaction was swift; on December 18, 129 B-52s took off from Guam and Thailand, destination North Vietnam.

What was that awaiting the world’s most formidable bombers were the world’s most formidable air defenses.

‘America’s fortress’

At the time, the B-52 bomber was the gold standard of aerial firepower.

The eight-engine Stratofortress, some of which could carry more than 80,000 pounds of ordnance, first flew in 1954 and was designed to be an intercontinental bomber that could deliver nuclear payloads anywhere in the world.

Alongside intercontinental ballistic missiles and ballistic missile submarines, it formed one prong of the nuclear triad America hoped would deter any possible atomic war with the Soviet Union.

But in the 1960s it began to take on more conventional bombing missions as the US enlisted its help in its struggle against Soviet-supported communist expansion in Indochina.

The B-52s were able to fly higher than the naked eye could see, making its attacks both physically and psychologically devastating as its massive payloads would arrive seemingly from nowhere.

“(Nixon) wanted maximum psychological impact on the North Vietnamese, and the B-52 was airpower’s best tool for the job,” historian T.W. Beagle wrote in a 2001 report for the US Air Force’s Air University Press.

Still, as formidable as the B-52s were, the tactics they employed hadn’t changed much since World War II.

And for some of their crews, that would prove fatal.

Fly into the danger zone

North Vietnam’s air defenses were backed by Soviet-made SA-2 antiaircraft missiles, capable of shooting a 288-pound warhead to altitudes of 60,000 feet at more than three times the speed of sound.

US aircrew said they looked like telephone poles with lights and would illuminate the entire night sky.

On the first night of Linebacker II, North Vietnam fired 200 of them at the attacking US bombers and at least five of those missiles found their targets.

Three B-52 were brought down, and two others were damaged.

As if that were not daunting enough, the crews back at U Tapao were left in no doubt that more casualties were expected.

Etched into Wallingford’s memory are the words of a general that day.

“He said, ‘Well, we thought we were going to lose a lot more of you than we did,’” Wallingford said. “That wasn’t a very motivational speech.”

An open US playbook

The disastrous first day of the B-52s might have hit morale in U Tapao and Guam, but it had the opposite effect in Hanoi.

“We all feared the B-52 at first because the US said it was invincible,” Nguyen Van Phiet, a North Vietnamese missile gunner credited with downing four B-52s during Linebacker, told Smithsonian magazine in 2014. “But after the first night, we knew the B-52 could be destroyed just like any other aircraft.”

On the second night, the B-52s fared better with only two damaged out of 93 flying and none lost.

But by night three, the North Vietnamese gunners had seen the US playbook and knew it as well as their US opponents.

The bombers would fly in long columns over predetermined tracks and after releasing their payloads would make banked turns to head home – at which point their electronic jamming equipment (meant to thwart antiaircraft batteries) would be facing skyward, leaving them vulnerable.

“We were told for the last two minutes of the bomb run to stay straight and level which means you are a sitting target,” Wallingford said.

Opening the doors to the bomber’s cavernous bomb bay increased its radar signature even further, he said. “It’s kind of a losing proposition.”

Taken together, this meant the raids were “so predictable that any enemy would be able to knock you down kind of like the arcade at the carnival,” Ron Bartlett, another B-52 electronic warfare officer, told a Distinguished Flying Cross Society podcast.

On night three, six B-52s crashed to the ground.

Those losses did not go down well with the American public or Nixon, who “raised holy hell” about the bombers taking the same routes every night and who feared the heavy loss of America’s mightiest warplanes would “create the antithesis of the psychological impact (he) desired,” according to Beagle.

From the following night, the bombers were told to approach their targets from varied altitudes and directions; and not to fly single file or over targets they’d just hit.

Over the final seven days of bombing, only six more B-52s were shot down.

Was it all in vain?

At some point after day eight of the bombings, North Vietnam informed the US it was ready to resume peace talks in Paris.

This justified the operation, Nixon claimed. But many experts have since suggested this would have happened anyway and that a more patient Nixon could have avoided the horror and bloodshed on both sides.

They say that by late 1972 Hanoi’s war effort was already on shaky ground. Resources were low, and it would not have been able to sustain its war effort much longer.

“By the time of Linebacker II, the North Vietnamese were prepared to meet the demands outlined in Paris to get the United States out of the war,” wrote Brian Laslie, command historian at the US Air Force Academy, in his 2021 book “Air Power’s Lost Cause.”

Asselin, meanwhile, believes the North Vietnamese Politburo agreed on December 18, just hours before the bombing began, to let Washington know they would return to the peace talks.

“Unfortunately, before it could relay its decision to the White House, it was already too late; Nixon had reached the end of his tether. At 8 p.m., Hanoi time, that same day, the United States commenced its most savage bombing of the North to date,” Asselin wrote.

Winners and winners (and losers)

What is not in dispute is that the Paris Peace Talks resumed on January 8, 1973, and an accord was signed on January 27 that ushered in the beginning of the end to US involvement in the war.

It was signed not only by the US and North Vietnam, but also by the South Vietnamese who had been convinced by Linebacker that, “if North Vietnam attacked again the US would return to bombing Hanoi,” said Peter Layton, a fellow at the Griffith Asia Institute in Australia and a former Royal Australian Air Force officer.

With the accord behind them, both Washington and Hanoi then claimed themselves the victors of Operation Linebacker II.

Airman Wallingford and others are emphatic about a US victory.

“It was the operation that ended the Vietnam conflict and that freed our 591 POWs,” he said. (Those American prisoners of war were released in February and March after the accords were signed.)

But even in America, some had their doubts.

Robert Hopkins, a former US Air Force pilot, cautioned against falling into the “Linebacker II was a success trap,” saying that for the B-52 pilots it “deeply hurt morale for years to come.”

There was a more immediate problem, too.

Three years on, with the Communist forces largely replenished and US forces largely out of Vietnam, Hanoi launched the large scale invasion of the South that led to the fall of Saigon on April 30, 1975.

“Linebacker II ended the American phase of the war, but its impact only lasted three years. Linebacker II did not bring lasting peace,” Layton said.

In Hanoi, “the story of the events of late December 1972 was a tale, not of massive loss and destruction, but of heroic resistance by Northerners,” wrote the historian Asselin.

“In fact, the toll on the US forces had been such that it had forced Nixon to beg Hanoi to resume the peace talks, and to unilaterally and unconditionally end the bombing,” he wrote.

Or as Kissinger, the US national security adviser of the time, was reported to have said:

“We bombed the North Vietnamese into accepting our concessions.”

source CNN

Comment