When Amartya Sen arrived at Cambridge as a student in 1953, his landlady, Mrs Hangary, worried that his brown skin would stain the bathtub.

“By the end of his tenancy, she had become a campaigner for racial equality,” writes Edward Luce, one-time Delhi-based South Asia bureau chief of the Financial Times and now the newspaper’s US national editor.

“‘She went from racist to jihadi for equality,’ Sen says, chuckling. ‘I adored Mrs Hangary’,” writes Luce, who recently interviewed the Nobel laureate ahead of the publication of his long-awaited memoirs.Advertisement

The economist’s book, Home in the World, is scheduled to be released in the UK by Allen Lane on July 8.

This is how the publishers have summed up the book: “Where is ‘home’? For Amartya Sen home has been many places — Dhaka in modern Bangladesh where he grew up, the village of Santiniketan where he was raised by his grandparents as much as by his parents, Calcutta where he first studied economics and was active in student movements, and Trinity College, Cambridge, to which he came aged nineteen.

“Central to his formation was the intellectually liberating school in Santiniketan founded by Rabindranath Tagore (who gave him his name Amartya) and enticing conversations in the famous Coffee House on College Street in Calcutta. As an undergraduate at Cambridge, he engaged with many of the leading figures of the day. This is a book of ideas — especially Marx, Keynes and Arrow — as much as of people and places.”

“In one memorable chapter, Sen evokes ‘the rivers of Bengal’ along which he travelled with his parents between Dhaka and their ancestral villages. The historic culture of Bengal is wonderfully explored, as is the political inflaming of Hindu-Muslim hostility and the resistance to it.

“In 1943, Sen witnessed the Bengal famine and its disastrous development. Some of Sen’s family were imprisoned for their opposition to British rule: not surprisingly, the relationship between Britain and India is another main theme of the book. Forty-five years after he first arrived at ‘the Gates of Trinity’, one of Britain’s greatest intellectual foundations, Sen became its Master.”

No doubt the book will be reviewed widely but ahead of publication, Luce met Sen at his home in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Sen is based at Harvard University where he is Thomas W. Lamont University Professor, and Professor of Economics and Philosophy.

It being July, Sen should really be in Cambridge in England where he likes to spend the summer. He still has rooms at Trinity College, where he first arrived as an undergraduate in 1953 (after Presidency College in Calcutta), became a Fellow and eventually served as Master from 1998 to 2004.

Luce writes: “The first non-white head of a Cambridge college when he became Master of Trinity in 1998, he has taught at Harvard, Oxford, Delhi, the London School of Economics, with brief spells at too many more to mention. He was also the first head of India’s Nalanda University, the moribund Buddhist institution (arguably the world’s first university), which was founded by Emperor Ashoka in the third century BC and brought back into existence in 2014.”

He adds: “Very little of this happened before 1963.”

This is when the memoirs end.

But Luce also underlines: “Yet, minus one or two romantic dramas, his memoir presages all that was to follow. Sen, who has been married three times and has two children from each of his first two marriages, tells me it might be impolitic to write a second that would touch on their lives. He has been married since 1991 to Emma Rothschild, the distinguished historian who now holds a chair at Harvard. It seems that one volume will have to suffice.”

Home in the World is listed among the FT’s “best books of the week”.

Sen expresses relief: “I am so glad finally to get this book off my hands.”

That Sen has serious misgivings about the direction India is taking under Narendra Modi is well known.

Luce writes: “Today’s Indian rulers, Sen fears, are attempting to stamp out its tradition of openness. The BJP is rewriting history to excise the secular legacy of the early Moghuls, such as Akbar, who had as many Hindus at court as Muslims, and, of course, Ashoka, who preached tolerance for all beliefs.”

Sen says: “India has a long history of pluralism that is now under threat. Akbar’s court was thriving in the late 16th century when they were burning heretics in Rome’s Campo di Fiore.”

According to Luce, “Sen attaches some of the blame to V.S. Naipaul, the late Nobel Prize-winning Trinidadian Indian, who depicted the history of India’s Muslim dynasties as a dark night of temple-razing oppression.”

Luce reminds readers that “Sen resigned from Nalanda in 2015 after Narendra Modi’s Hindu nationalist BJP had taken office and blocked money to a university that it suspected was anti-Hindu. Modi’s government denied Nalanda permission to celebrate Buddha’s birthday, even though the philosopher-prince gave the world a creed that was quintessentially Indian.

“A few years ago, Sen was to appear on the BBC’s Hard Talk programme and noticed he was described on the teleprompter as a ‘Hindu scholar’,” Luce writes.

He quotes Sen as saying: “I said, ‘Are you going to take this off, or shall I leave?’ They took it out.”

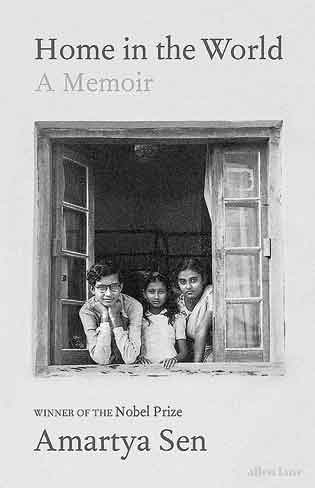

Luce explains: “The title of Sen’s book is drawn from a Tagore novel, The Home and the World, which is about the complexities of India’s struggle against western domination that was also immortalised in a Satyajit Ray movie of the same name. To Sen, the title evokes the secular, intellectually curious and tolerant climate in which he was raised. Sen recalls that visitors to the ashram included Eleanor Roosevelt, Chiang Kai-shek and, of course, Mohandas Gandhi, who was murdered by a Hindu nationalist. The cover of Amartya Sen’s memoirs, Home in the World

The cover of Amartya Sen’s memoirs, Home in the World

“Sen’s story as a cosmopolitan in the world has not lessened his sense of Indianness. Though he has lived abroad since 1971, he only has an Indian passport. Before the pandemic, he would visit Santiniketan up to five times a year, where he keeps a house (aided by a lifelong right to free first-class travel on Air India – a massive perk that followed his Nobel award).”

Luce makes it clear that Sen is now in poor health. “It took 20 minutes to manoeuvre Amartya Sen from his Harvard home to a restaurant at the Charles Hotel two minutes around the corner. At 87, Sen’s mind remains as sharp as when he won the Nobel memorial prize in economics in 1998. But his body is painfully frail.

“In 2018, Sen underwent 90 days of radiation therapy to treat prostate cancer. He suffered from mouth cancer as a student in Kolkata in the early 1950s. His Indian doctors gave him a one in seven chance of surviving beyond five years. He confounded them all.

“Much like Vladimir Nabokov’s dental agony, Sen’s memoir… is pockmarked with Sen’s lifelong physical ailment. In more ways than one, his life has been a triumph of mind over matter.

“Sen has had one knee replaced but is not yet robust enough to replace the other, which means he is constantly unbalanced and suffers cramps from poor circulation. Only his cerebrally sunny demeanour seems unscarred. ‘I haven’t lost any of my teeth,’ Sen tells me with a lopsided grin.”

Luce reassures readers that Sen’s “odyssey is by no means complete. He plans to write monographs on various pet themes. These include the future of higher education, which would include spicy critiques of Harvard’s administrative shortfalls. The university’s managers, whom Sen mischievously likens to the autocratic British Raj, spend more time with donors than scholars.

“‘They are too distant from the academia they are supervising,’ he says. ‘As Master of Trinity, I had lunch with every undergraduate’.”

Luce surveys Sen’s home in Harvard: “Looking around, it strikes me that Sen is more than an economist, a moral philosopher or even an academic. He is a lifelong campaigner, through scholarship and activism, via friendships and the occasional enemy, for a more noble idea of home – and therefore of the world.

“In this age of identity politics, this Bengali savant refuses to be defined by labels. ‘Home and the world are the same thing for me,’ he says. ‘It always was.’ Our colour, our religion, our gender, our nationality – these are mere facets of our complex selves.”

The FT’s standfirst (a brief introductory summary) to the interview reads: “Home in the World by Amartya Sen – citizen of everywhere.”

Comment