By Lindsay Baker9th October 2020How we handle change is the essence of our existence and the key to happiness, particularly in our current times of uncertainty. In the first of a new series, The Art of Living, Lindsay Baker explores the philosophy of change.

“Life is flux,” said the philosopher Heraclitus. The Greek philosopher pointed out in 500 BC that everything is constantly shifting, and becoming something other to what it was before. Like a river, life flows ever onwards, and while we may step from the riverbank into the river, the waters flowing over our feet will never be the same waters that flowed even one moment before. Heraclitus concluded that since the very nature of life is change, to resist this natural flow was to resist the very essence of our existence. “There is nothing permanent except change,” he said.

Or, as the novelist Elena Ferrante said recently: “We don’t have to fear change, what is other shouldn’t frighten us.” If we can learn to handle this constant flux, we can handle life itself – which, several millennia on from Heraclitus, in our currently uncertain and fast-changing times, feels particularly resonant. Since humankind has existed, many great artists, writers and philosophers have grappled with the notion of change, and our impulse to resist it. “Something in us wishes to remain a child… to reject everything strange,” wrote the 20th-Century psychologist and author Carl Jung in The Stages of Life, echoing Heraclitus. For these thinkers, a refusal to embrace change as a necessary and normal part of life will lead to problems, pain and disappointment. If we accept that everything is constantly changing and fleeting, they say, things run altogether more smoothly.

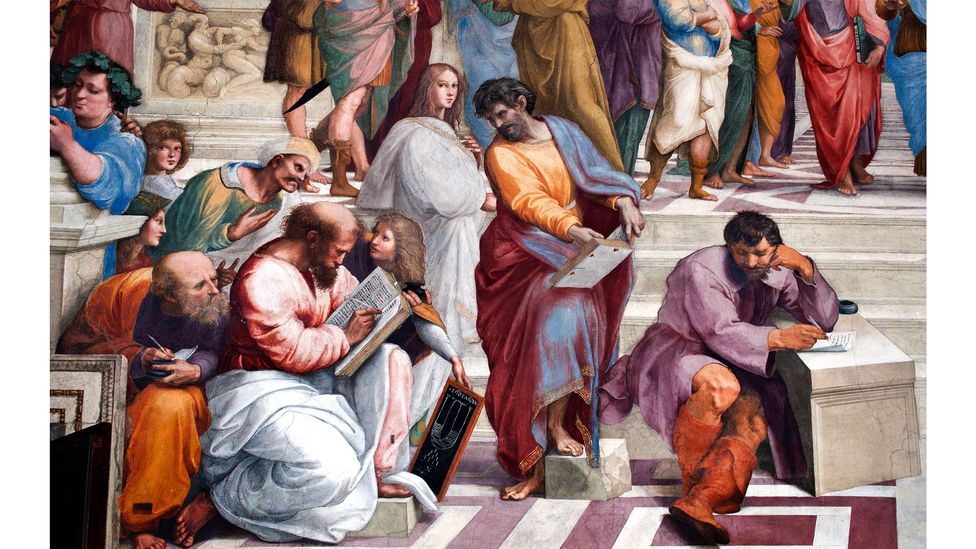

The philosopher Heraclitus (right, at desk) is featured in Raphael’s masterpiece The School of Athens (Credit: Alamy)

So does the ‘life is flux’ theory mean we must be resigned in a fatalistic way to all the challenges, changes and crises life throws at us? Not necessarily, says John Sellars, author of new book Lessons in Stoicism and philosophy lecturer at Royal Holloway, University of London. According to Sellars, Heraclitus’s theory is less about resignation and more about “acceptance”.

Change is a favourite subject of Stoicism, a school of Hellenistic philosophy (partly inspired by Heraclitus) that is informed by a system of logic and its view of the natural world. To be ‘stoical’ in the popular imagination is to endure hardship without complaint, to ‘grin and bear it’. But the philosophy is more nuanced than that. In his book, Sellars weaves together the thoughts of three Stoics – Seneca, Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius – showing how their ideas can help us today.

Everything changes, the question is, do we change with it? – John Sellars

“Stoics believe that nothing is stable, and we need to come to terms with that. The natural world is made up of a series of processes that are changing, but if we want to live happily with nature we have to live in harmony with it.” And in fact, he says, Stoicism is not so much about resisting change as facing up to it. Everything changes, the question is, do we change with it?” says Sellars. “Stoics say we don’t have any choice, we can’t fight it.”

This idea is echoed throughout art and literature. British author Virginia Woolf, who famously wrote in an interior-monologue style that itself captured the mutability of thought, wrote: “A self that goes on changing is a self that goes on living.” In one of her most unconventional works, the prose poem The Waves (1931), Woolf follows the consciousnesses of six friends, starting from their childhoods. The characters enter new phases of life that are filled with novelty and lack of certainty. A fluid narrative voice shifts subtly between their different points of view, as all of them struggle in some way to define themselves. Woolf presents them all as in a perpetual process of change and metamorphosis throughout the story, as all of us are in life.

Change was one of Woolf’s obsessions. In her earlier, playful novel Orlando (1928), she tells the story of a nobleman in Elizabethan times who, halfway through the novel, awakes to find that he has become a woman. “Change was incessant,” writes Woolf in the novel, “and change perhaps would never cease. High battlements of thought, habits that had seemed as durable as stone, went down like shadows at the touch of another mind and left a naked sky and fresh stars twinkling in it.”

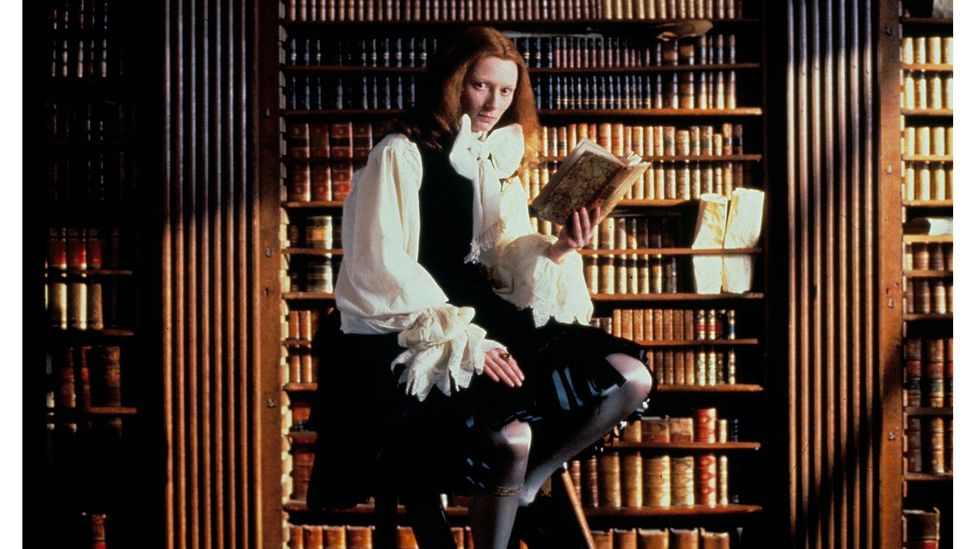

Orlando, the 1992 film based on Woolf’s novel, is the story of a nobleman who becomes a woman (Credit: Alamy)

Woolf – although she was in the end unable to conquer her demons – was an avid keeper of a journal, and wrote down her innermost thoughts aiming to work through her feelings. She shared this habit with many significant writers and thinkers, among them Susan Sontag, Joan Didion, Oscar Wilde – and Stoic Marcus Aurelius. In fact, practising Stoics today still recommend the keeping of a journal, in order to steel themselves for whatever the day ahead may throw at them, and later in the day, to review their actions. The idea is to train yourself to be as prepared as possible, given the changeability of life.

Maybe this is why Stoics have gained a reputation for a no-nonsense ‘stiff upper lip’. “There’s some basis in reality, yes,” concedes John Sellars. “It’s partly about toughening up and training, since learning how to deal with adversity means it doesn’t feel so hard. But it’s not about controlling or repressing – the idea that Stoicism is just about remaining resolute misses something important.”

The only lasting truth

Is cool rationality the key to negotiate change, then? “The goal is to lead a good, happy life,” says Sellars, “and to get into the right place to experience genuine joy, not a flat emotion.” The Stoics advise appreciating things now but also understanding that they are not forever. “Don’t be afraid of uncertainty.” In this sense, says Sellars, Stoicism has broad parallels with Buddhism. “Things are changing, live in the present moment, don’t have strong attachments to external things.” This may sound a little unfeeling, cold even – but it’s not, insists Sellars. “Because like Buddhism, Stoicism also advises to feel compassion for all sentient creatures, and to have natural affinities, and not to be unfeeling or emotionless.”

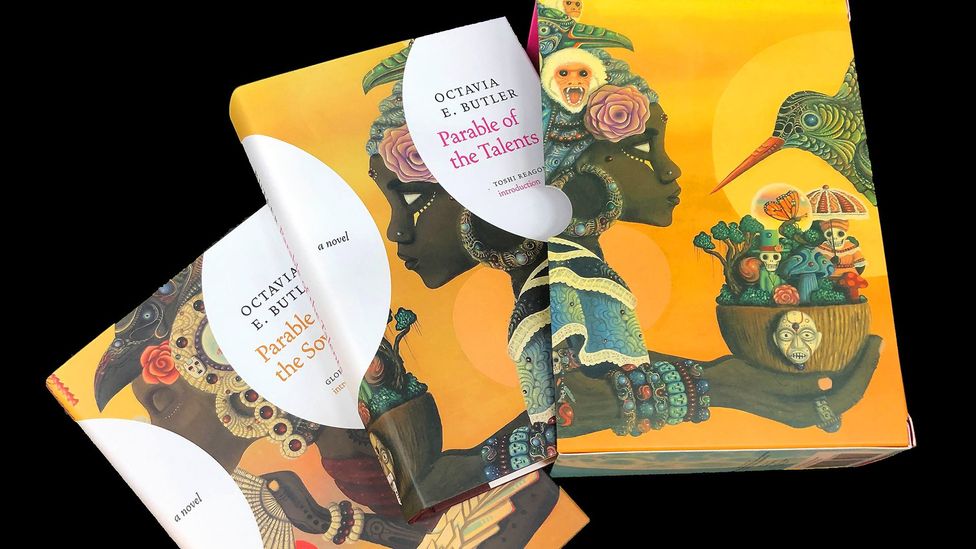

In the speculative novel Parable of the Sower, the connection between life, change and nature is a central theme (Credit: Seven Stories Press)

In her speculative, sci-fi novel Parable of the Sower (1993), Octavia E Butler presents a protagonist, Lauren, who founds a religion she calls Earthseed, and who has visions of change as the animating force of the cosmos. Lauren notes down her visions as epigrammatic statements: “All that you touch you Change. All that you Change changes you. The only lasting truth is Change. God is Change.” She also makes the same connection between life, change and nature as Heraclitus did in his ‘life is flux’ theory. Butler writes: “Seed to tree, tree to forest; Rain to river, river to sea; Grubs to bees, bees to swarm. From one, many; from many, one; Forever uniting, growing, dissolving— forever Changing. The universe is God’s self-portrait.”

All that you touch you Change. All that you Change changes you. The only lasting truth is Change – Octavia E Butler

And Lauren’s vision for the world is one where good conquers evil, and where kindness conquers cruelty. As US author and academic Rebecca Raphael notes in an essay on Butler’s work: “Lauren joins these Heraclitus-like ideas with ethical injunctions to attend well and to shape consciously the change in which one is implicated. There is nothing supernatural about Earthseed’s Change: neither a providence nor an otherworldly eschatology, it is a call to responsibility for the shifting patterns of one’s world.”

Lauren’s religion, Earthseed, contains aspects of both Stoicism and Buddhism. As Raphael puts it: “The component ideas of Earthseed are not new. It has elements of Buddhist metaphysics, of Judaic world-shaping through ethical action, and of Stoic focus on what, however small, one can actually do in the moment. It has no contempt for a social or religious out-group, but instead fosters kindness in a violent world, in order to prepare humans for life on other planets.”

So in our current crisis, how would the Stoics advise us to approach change – not only now but also in the future, whatever that may hold? “We must distinguish between things that are in our control, and things that are not,” says Sellars. “You can self-isolate and social distance, and do those things as an act of calm rational caution, not motivated by panic, fear or anxiety.”

The Modern Stoicism movement holds an annual Stoic Week, in which those involved are challenged to focus on the process not the outcome, and to face up to the reality that adversity is part of the normal course of life; that we can learn from adversity, and learn through failure. Adversity, in other words, is a learning experience.

This too shall pass

A medieval prophet asked a wise man for a message to keep him safe. His answer? “This too shall pass”. It was a phrase used in recent months by the actor Tom Hanks in connection with the Coronavirus pandemic, and it’s the name of a book out recently by psychotherapist Julia Samuels. In This Too Shall Pass: Stories of Change, Crisis and Hopeful Beginnings, Samuels relates (anonymously) some of her clients’ stories. “Every person who has walked through my door has had a problematic relationship with change,” she tells BBC Culture. “Change is the one certainty of life, and pain is the agent of change, it forces you to wake up and see the world differently, and the discomfort of it forces you to see the reality of it. It’s through pain that we learn, personally and also universally.”

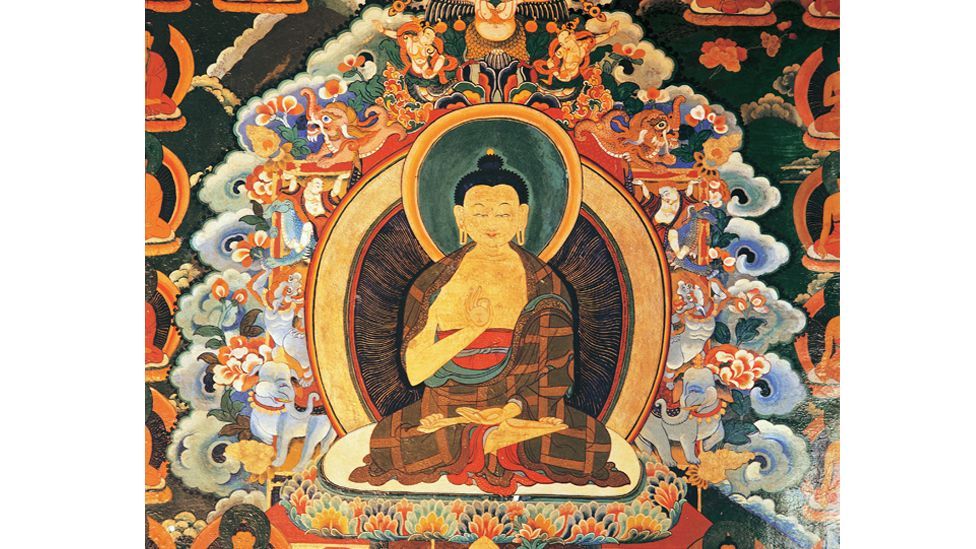

To live in the present moment in our changing world is one of Buddhism’s tenets (Credit: Alamy)

Samuels says that when the current pandemic first struck, a lot of us were “numb, shocked and anxious. It was like the scary Jaws music coming, you can block it but in the end you have to pay attention, you have to shift and change”. She chose the phrase ‘This too shall pass’ for her book’s title because “you have to go with change and crises to come out the other side. You may not believe that it will ever end. In winter you may not believe that summer will come, but it does.”

Accepting change also makes you better at it, she says. “It’s the paradox that the more you allow yourself to accept that change is inevitable, the more likely you are to change intentionally and adapt.” Change can be an engine of progress.

Samuels is all for accepting the flux of life and nature, and for facing up to the biggest change any of us ever experiences, our own mortality. “I think what we don’t look at grows inside us, so it’s good to have conversations with each other about the end of life. The things you don’t talk about could haunt you and make everything more complicated. Life is precious but it’s good to accept that it’s limited.”

Change is the basis of all history, the proof of vigour – Jenny Holzer

It’s been more than half a century since Sam Cooke’s powerful and optimistic civil-rights anthem A Change is Gonna Come. Yet it’s a song that remains as timely as ever. And it’s been nearly 40 years since the US conceptual artist Jenny Holzer’s iconic lithograph Inflammatory Essays, with its rousing message: “Change is the basis of all history, the proof of vigour”. The provocative artwork, created in the early 1980s, is full of the US artist’s trademark dogmatic, pithy truisms. Recently exhibited at London’s Tate Modern, it still feels resoundingly relevant today. “Upheaval is desirable because fresh, untainted groups seize opportunity,” is another phrase from the artwork, along with “The decadent and powerful champion continuity”; “Slow modification can be effective; men change before they notice and resist”; and “The worst is a harbinger of the best”.

The current crisis – and the fight for racial and social equality – make Holzer’s words feel all the more resonant. And with many communities showing solidarity and support, it seems that qualities such as courage, resilience, compassion, empathy – and a sense of fairness and justice – still can be found. How will we look back on this time of turmoil, change and upheaval? Will we come out of this situation with a deeper understanding and an enhanced perspective on humankind, our priorities and our values? With our ‘vigour’ proved?

Source BBC

Comment