Kathmandu, August 19:

- During the last war between China and India, New Delhi interned thousands of Chinese-Indians in a POW camp, fearing they represented a ‘fifth column’

- Amid a new border dispute that has claimed dozens of lives, many fear they will be scapegoated once again – and are asking Justin Trudeau to help

On the first of July this year, 15 days after dozens of soldiers died in hand-to-hand combat between Indian and Chinese troops in the Galwan Valley of the Himalayas, a letter made its way to the Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau.Over three pages, it addressed the border dispute between the two Asian giants from a unique point of view, one that has gone largely unreported in the press: that of the Chinese-Indian community.

After greeting Trudeau, and praising his stance on social justice, the letter urged him to view this community’s plight through the prism of history.

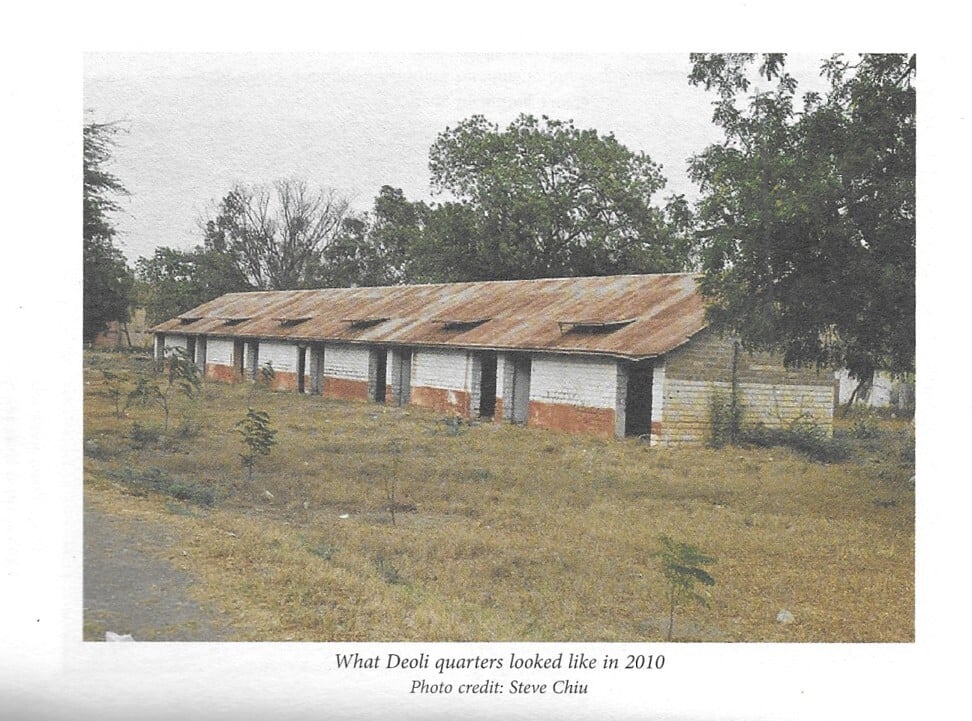

It reminded him of how during and after the 1962 war that India lost to China, thousands of Chinese-Indians had been interned in a POW camp left over from World War II in Deoli, a dusty town in Rajasthan.

The internment camp in Deoli. Photo courtesy of Joy Ma and Dilip D’Souza

New Delhi had been suspicious that this community of about 50,000, based mostly in what was then called Calcutta, could be a “fifth column” sympathetic to the Chinese cause. Among the 3,000 Chinese-Indians it interned were old men, women and children. Families were often separated; in cases where one spouse was ethnically Indian, the other Chinese, the Indian would be spared by the government. Properties were confiscated.

The letter pointed out that even after the war ended, the internments continued; it was not until 1967 that the last inmates were released.

In plain terms, the lives of people who had once been very much a part of their communities – working as dentists, beauticians, shoemakers and restaurateurs – were upended completely.

Even after being set free, they were barred from government jobs, sealing their status as second-class citizens in the country many were born into and chose to live, love, and work in.

They left India in droves, many heading for Canada, but also for Australia, America and Hong Kong – where a few thousand remain today. Two to three thousand went straight from the camp in Deoli to China in the 1960s, at the invitation of the Chinese government.

Today, no more than 5,000 Chinese-Indians live in India. Around 3,000 live in Kolkata, where the community settled two to three centuries ago under the British, and many of the rest are spread across the seven states in India’s northeast, particularly in Assam, close to the border with China.

After narrating this painful episode, the letter turned its attention to the present border dispute in the Galwan Valley – a dispute that shows little sign of ending, with the Indian Foreign Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar saying last week that India would “stand its ground” for as long as it took.The letter said the stand-off was not only “unresolved” but the “worst ever” between the two countries, pointing out that Indian politicians had called for bans on Chinese food and goods. It asked the Canadian government to monitor the situation and provide refuge if Chinese-Indians were forced to leave the country once again.

It included a startling claim: “The Chinese community in India is terrified.”

TERRIFIED?

The letter was signed by Ying Sheng Wong, the president of the Ontario-based Association of India Deoli Camp Internees (AIDCI), 1962, who was himself sent to the internment camp as a teenager. This Week in Asia was unable to reach Wong, but the letter is posted on the AIDCI’s Facebook page and members of the association confirmed it had been sent to Trudeau, who has not yet responded.

Members of AIDCI started meeting in the 1980s and formalised as an association in 2012, the 50th anniversary of the war. In 2017, they demonstrated outside the Indian Embassy in Ottawa to demand an apology for the “humanitarian wrong” they suffered. Today, the group has around 300 to 500 members.

However, not everyone within the community agrees with the AIDCI’s claim.

“Just like you would not feel the same way as your parents or grandparents about the Partition of India, the younger generation of Chinese-Indians does not feel the same about what happened in the past,” said Robert Hsu, secretary of the Chinese-Indians Association in Kolkota.

While admitting that tensions on the border were a worry, he denied that the community was living in dread of renewed persecution.

Indian media reports of 40 Chinese soldiers’ deaths ‘false information’, Beijing says

Indian media reports of 40 Chinese soldiers’ deaths ‘false information’, Beijing saysHe did, however, suspect that the latest tensions had stalled a plan known as The Cha Project between a Singapore-based company and the state government to redevelop Kolkata’s Chinatown as a heritage area and tourist hub. “It was a slow-moving project in any case,” said Hsu.

There are two parts to the project: a US$65 million New Chinatown urban development project and a US$655,000 to US$900,000 Old Chinatown that would include restaurants and a heritage walk.But Rinkoo Bhowmi of The Cha Project said it was still on track and denied it had been affected by China-India tensions. She said it had been slowed only by the outbreak of the coronavirus.

“It has not stalled completely. One of the reasons [it’s slow] is I’m sitting here in Singapore, I plan to move and spend more time in Kolkata, but it’s a bit difficult to follow up and we had a change in secretary of tourism and you’ve to do it all over again. There are multiple reasons why things are slow, but definitely not because of the relationship between India and China. We haven’t faced anything to do with that.”

Edward Chiu Minsen, who owns a shoe shop in Delhi’s premier shopping district of Connaught Place, said there was too little information about the border dispute to come to any conclusions yet.

“The newspapers are not giving the full picture, so we do not know what is going on there. As it is, we are not getting newspapers these days due to the fear of Covid-19,” said the mild-mannered businessman in his 40s. Asked about the letter to Trudeau, he said he had “no comment”.

However, Minsen, a third-generation Chinese-Indian whose grandfather was interned for four years in the camp, acknowledged that memories of 1962 lingered.

“For the rest of [my grandfather’s] life, he remained suspicious of all strangers, suspecting them of being intelligence agents,” Minsen said.

His father would go to the camp to visit his grandfather with food and other items every few months, he recalled, saying the period of forced inaction had given his grandfather diabetes, which lasted till he died in 1984.

But Chun Powhughe, who has a shoe shop at the upscale Jor Bagh market in Central Delhi, said the AIDCI was right. “We are terrified.”

PAINFUL REMINDER

The clash at the Galwan Valley – in which at least 20 Indian troops and an undisclosed number of Chinese soldiers died – was the bloodiest stand-off on the border since the 1962 war.

Opinions remain divided on who was the aggressor in 1962, but on that occasion India lost thousands of soldiers and the Chinese army overran Ladakh and India’s Northeast, including Assam, without even much of a fight. India was thoroughly embarrassed, despite China’s troops later withdrawing – on their own accord. No one disputes that India lost the war, even if there were small pockets of heroic resistance.

Powhughe, who is in his 60s, said the latest incident in Galwan had raised concerns with several of his relatives overseas. “They are worried for us,” he said.

Powhughe opened his shop in Central Delhi at the start of this month. He drives to work from the suburbs and is careful not to venture into “unfamiliar areas”.

“I have not faced any slurs or taunts but I have been at the receiving end of hostile stares from large groups. Within the family we advise each other, especially youngsters, to keep their heads down, and not respond to any provocations.”

In 1962, Powhughe’s family had been lucky to avoid internment. (Those most at risk of being interned were living in West Bengal and Assam and, to a lesser extent, Delhi).

However, they did not avoid scrutiny altogether. During the war and afterwards, an intelligence agent watched over them; Powhughe jokes that they became friendly enough to offer to share their autorickshaw with the agent when he was trailing them.

Still, Powhughe’s fear of persecution remains – and he is far from alone.

The Indian-Chinese Bollywood actor Meiyang Chang told a national newspaper that he had been harassed on social media during the border stand-off.

The report also said the community in Kolkata had been forced to join a rally in support of the Indian army. Various members of the community have received phone calls from relatives abroad concerned for their safety.

On social media, a restaurant owner from Kolkata appealed to people not to boycott Chinese food or be suspicious of Chinese-Indians. The post has been widely shared.Concerns were raised when the government of India recently dropped Mandarin from the list of foreign languages offered to students as part of the New Education Policy – a move widely seen as a response to the Galwan incident. New Delhi is also reportedly keeping an eye on India’s Confucius Institutes (China-backed educational NGOs aimed at promoting understanding of Chinese culture).

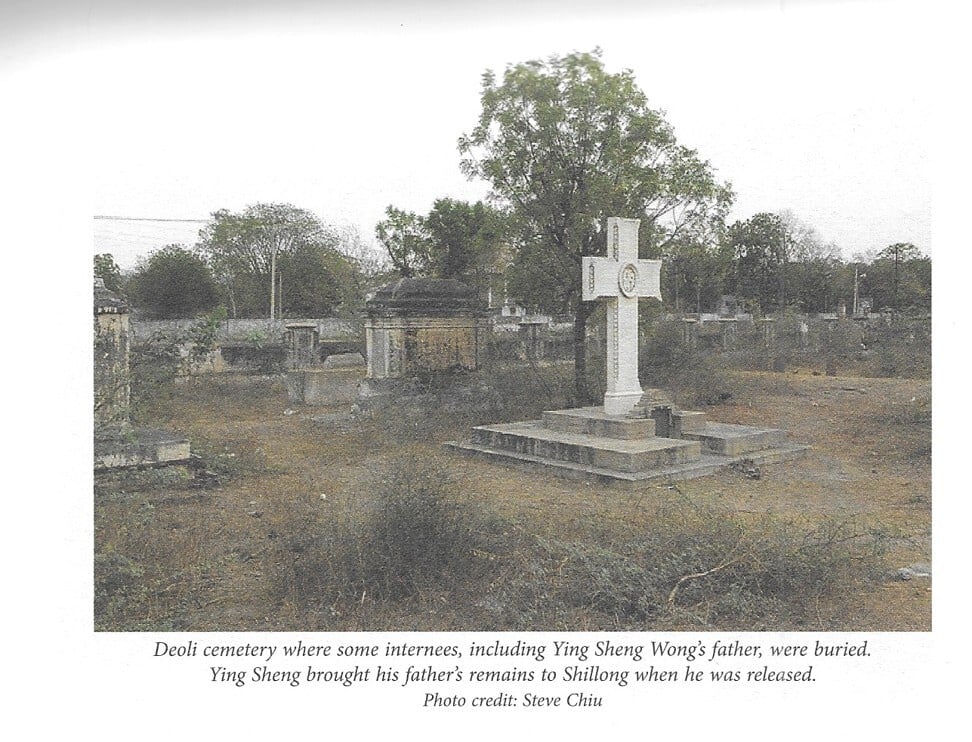

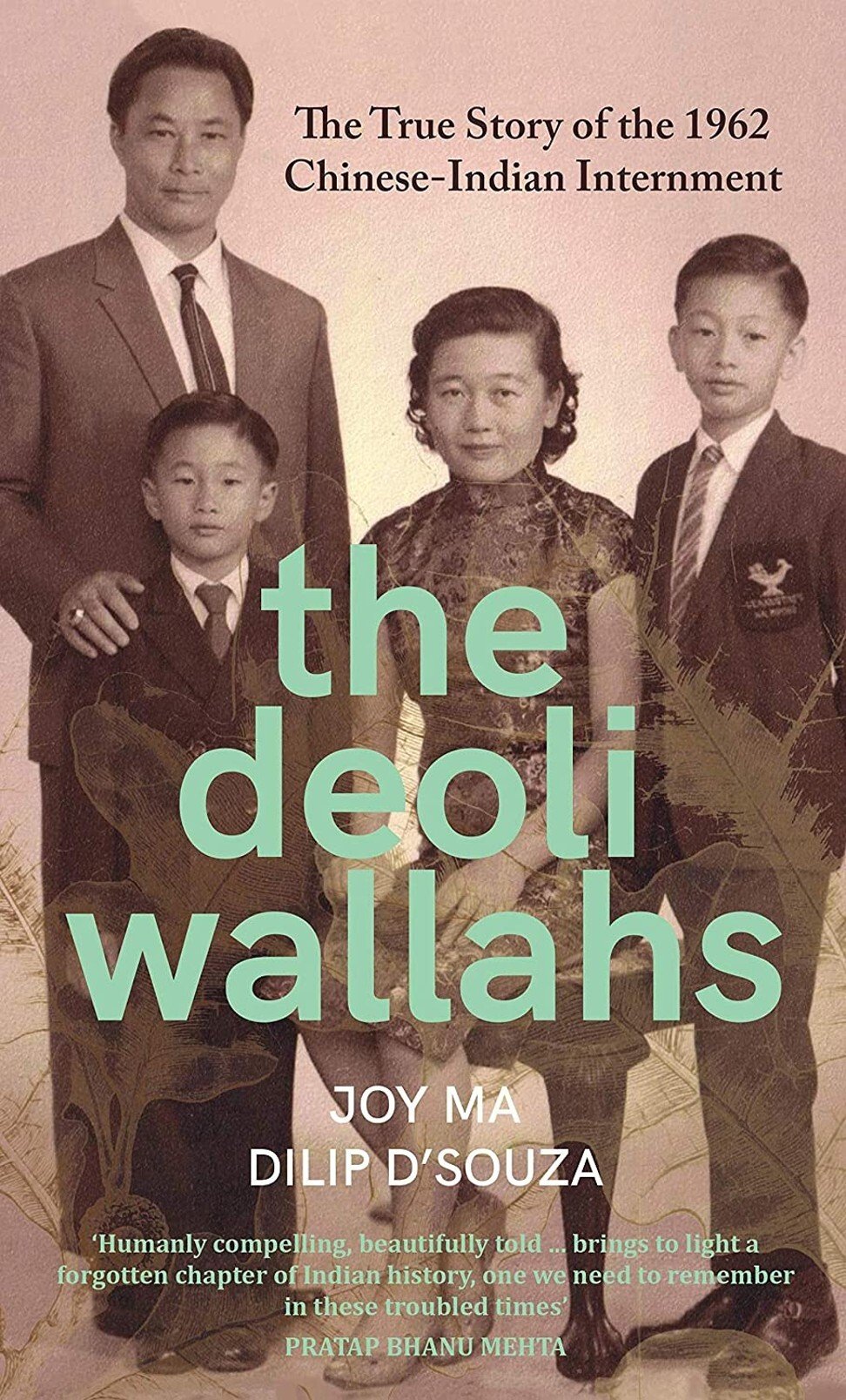

Author Joy Ma, whose book about the internees in the 1960s titled The Deoliwallahs is suggested as “required reading” in the letter to Trudeau, is among those calling for an official apology from New Delhi.

In Ma’s book, co-authored with Dilip D’Souza, former internees give heart-rending and chilling descriptions of the betrayal and sadness they felt when they were taken and the conditions under which they survived.

Ma narrates the story of a man who died at the camp and whose corpse was cut up for no particular reason, then stitched back together with brutal callousness by the camp doctors. The man, who “suddenly fell ill” of an undisclosed – but suspected minor – ailment was the father of the AIDCI president, Wong.

The cemetery where Ying Sheng Wong’s father was buried. Photo courtesy of Joy Ma and Dilip D’Souza

Asked if the community should also get reparations for financial losses, Ma said: “Let us have the apology first. Reparations are in the distant future.”

According to several accounts, the properties of those interned were taken over by the government, and auctioned. In many cases, property was looted and destroyed.

The AIDCI also wants a memorial to commemorate those who died to be built in Deoli.

Minsen said an apology from the government would be a good gesture for those from the “older generation” and the internees. “It will bring them closure.”

‘A TAG THEY CANNOT GET RID OF’

The Chinese started coming to India in the 18th century, and first settled in what was then Calcutta. They were mostly of Hakka origin; they specialised in the shoe trade as the community grew and, at one point, Calcutta’s Bentinck Street was full of their shoe shops.

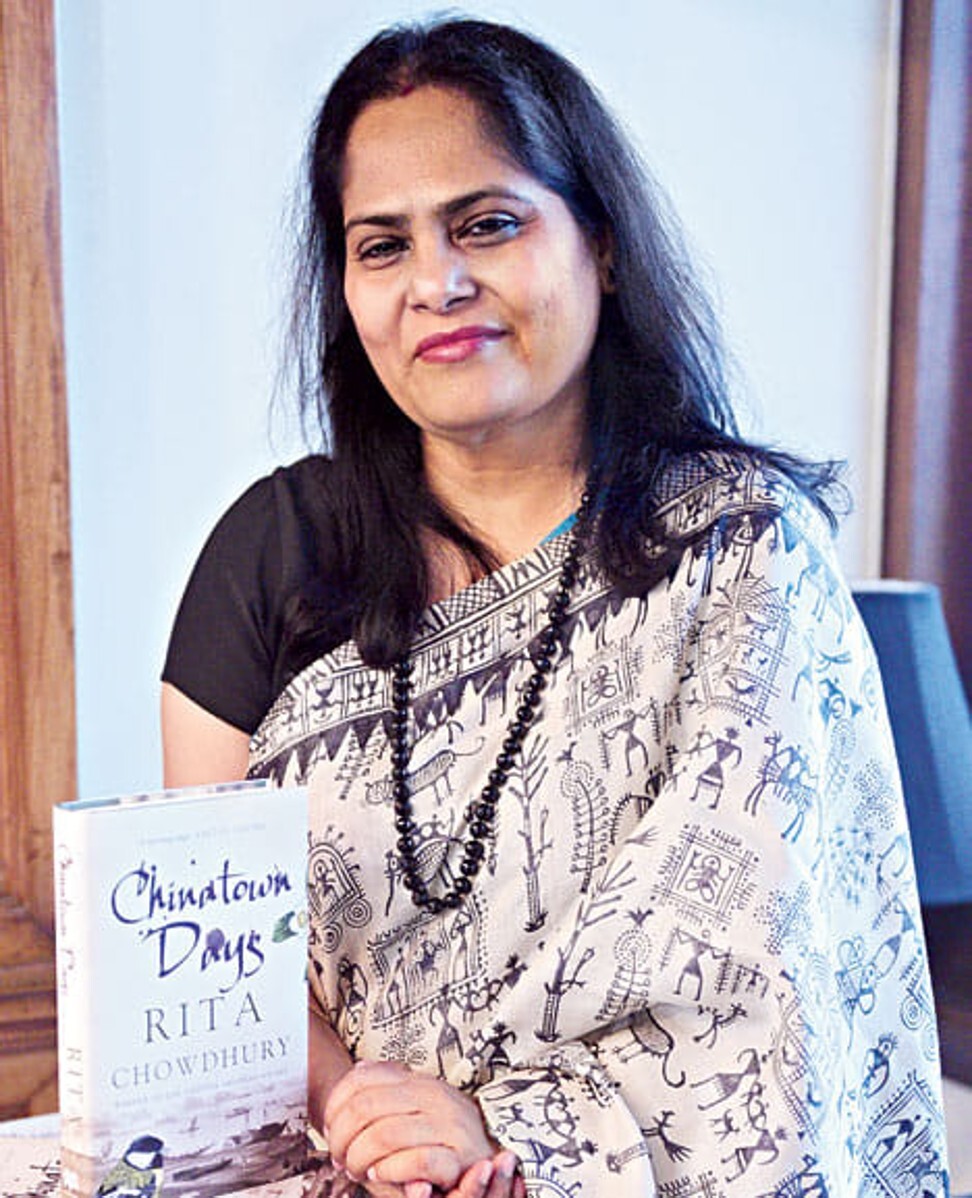

“The British also brought Chinese labourers to work in the tea gardens of Assam who were mostly Cantonese; carpentry was their main skill. It was a form of forced migration. Chaos and turmoil in mainland China also made them come to India,” said Rita Chowdhury, who has written a novel about the community, their experience in the Deoli camp and their subsequent exodus from India.

The novel is titled Makam, after a small town in Assam that was once a focal point for the Chinese-Indian community. Today, there are just a handful living in the town. “There used to be several Chinatowns near the tea gardens,” Chowdhury recalled.

Chowdhury, who keeps in touch with the community and calls them her “family”, said those living in Assam did feel afraid. “Anything happens on the border with China, they feel the heat. The locals start questioning them. This is wrong as they have been citizens of this country since they came before Partition. But the connection with China is like a tag they cannot get rid of.”

Indeed, in some quarters, suspicions against the community remain.

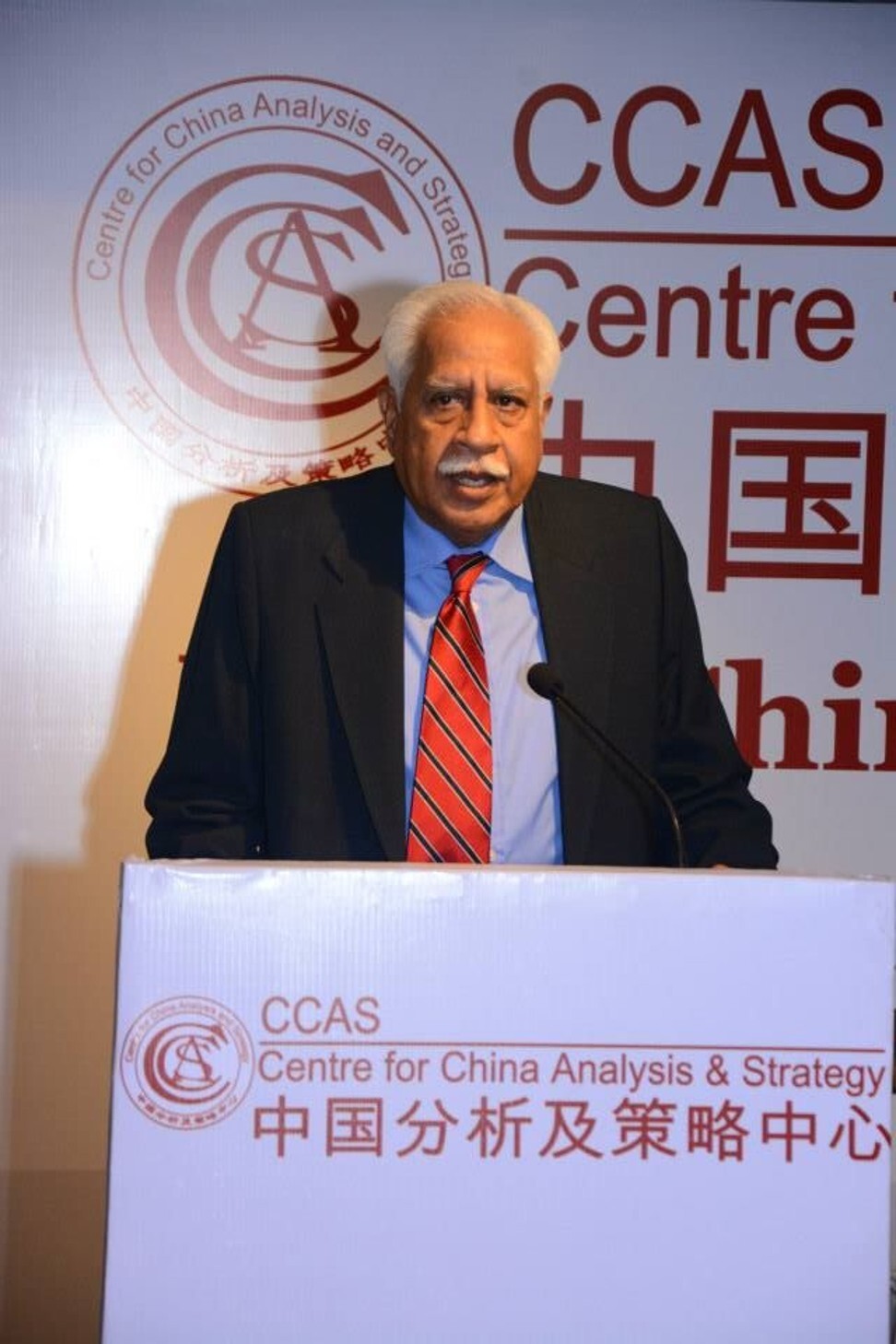

Jayadev Ranade, a former foreign intelligence officer who served in Beijing for many years and now runs a China-focused think tank in Delhi, China Analysis and Strategy, said an apology would be a tall order in the present climate.

“All governments take such measures to keep a check on minorities suspected of being a fifth column during wars and national emergencies. The Americans also detained the Japanese during the Second World War,” he said, while acknowledging that the practice gave rise to humanitarian concerns. (The American government has since apologised to the Japanese community).

His view chimes with similar opinions expressed by figures in the Indian military-political establishment who were quoted in Ma’s book.

Ranade, who has visited the community in Kolkata, questioned claims that the Indian government had taken property from those interned in Deoli.

“If they have grievances about their properties being taken over, they should contact the office which deals with enemy properties,” he said, referring to the Custodian of Enemy Properties for India. (This curiously named department was created for withholding properties from those who left for Pakistan after Partition 70-odd years ago, though it continues to exist to this day).

Still, for many Chinese-Indians, gaining an apology, recovering lost property or having a monument built are all secondary concerns. For the many who still love Indian culture despite living abroad and think fondly of India as their “motherland” – and China as their “fatherland” – it is primarily an emotional issue.

As Ma put it: “Indians should remember that Chinese-Indians are also Indians. They should treat them like good neighbours are supposed to treat one another.” ■

Comment